This essay is part of a 3-part series:

For almost all of human history, the vast majority of people had to rely on their brains and brawn to survive, through hunting and gathering and then agriculture. Animal power provided some assistance, but things started to change much more fundamentally once people learned to harness non-biological energy: wind, water, and then most impactfully steam.

With the advent of more plentiful energy and the development of more capable mechanical technology, the world changed. Jobs that used to be done with muscle power became easier to do with machines, and the roles of people in society changed as well.

Up until the 19th century, most workers’ jobs were simply to make food. But over the following century, agriculture became highly mechanized, and the fraction of people in industrialized countries that worked as full-time farmers plummeted:

At first, this agricultural revolution freed people to become other kinds of manual workers — especially in manufacturing and transportation, where they made the wide variety of physical implements needed for the new industrialized economy, and moved them to where they were needed.

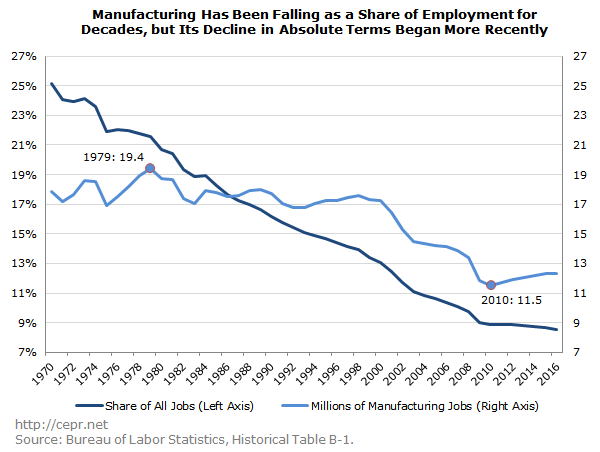

But over time, increasingly capable technology has caused the non-agricultural blue-collar part of the economy to require less and less labor as well. A factory that took 1000 people to run might now run with 30 technicians keeping an eye on the machines doing most of the work; a train that used to take 10 people to operate might now run with one.

Instead, in the industrialized world, people have increasingly become economically useful for their brains rather than for their brawn. A majority of US workers are now in white-collar fields, where they are paid for their knowledge and intellectual skills rather than for their strength and dexterity.

This process has had a wide range of effects on society. Physical strength and skill used to be a necessity for survival for most people. Now, an unusually strong American is as likely to be a hobbyist weightlifter as a manual laborer. Muscles used to be a tool; increasingly, they’ve become an ornament.

Instead, in developed countries like America, most people’s brains have become their most economically valuable assets. We’re becoming an economy where our interactions with the physical world are carried out by increasingly capable tools that require less and less physical effort from us — but where the management of an increasingly complicated world rests more and more on highly capable human brains.

Even our identities, to a significant degree, are tied up with our intelligence. We are homo sapiens, the wise human — we ascribe our preeminence as a species to our ability to understand and analyze the world around us.

It is that aspect of our existence that is now starting to change in the same way that our physical interactions with the world have been changing for the last 200 years.

Much like with draft animals before the Industrial Revolution, we’ve had some external assistance for our minds before now. Technology for communicating knowledge, from books to the Internet, has become more and more advanced over the centuries, giving us a longer and longer lever for our intellectual efforts. And computational technology, from abaci to today’s computers, has become more and more capable of doing routine but voluminous informational work quickly for us.

This has already changed the composition of the white-collar labor force: human “calculators” have been replaced by spreadsheets, and draftsmen by CAD programs. But bigger changes are now afoot.

We’ve reached a point in the development of artificial intelligence where its capabilities are extending into previously unimaginable territory. Computers used to need precise instructions for every task they could carry out, and they could only accept those instructions in their own arcane languages. Over the past year, this has changed — computers can now accept instructions in human language, written or spoken, and carry out those instructions successfully for even quite complex tasks.

Those capabilities are still far from perfect, but even if the abilities of AI were to be frozen at today’s level, white-collar work being performed by the full-time equivalent of many millions of people can, and will, be automated in the years to come using the technology that’s already available.

And future advances are inevitable as well. To date, most improvements in AI capabilities have come from deploying increasingly large amounts of computational power to train AI models on increasingly large amounts of data. Roughly speaking, every meaningful increase in AI capabilities has resulted from multiplying the amount of data and computational power used to train AI models by a factor of 10.

It’s likely that this approach will continue to bear fruit for at least one more “10x” cycle, which will likely take one to several more years. After that, data availability is likely to become a bottleneck — at that point, the latest AI models will have been trained on most extant codified human knowledge (books, the Internet, etc.) Feeding another “10x” cycle by synthesizing fake but realistic data, or gathering much more data from the real world, appears possible, but will likely be much slower than the current approach of using data that’s already available.

But in theory, it should also be possible to massively improve the data efficiency of training AI systems. Human brains have about 100 billion neurons, and humans can acquire a respectable education by learning information equivalent to the contents of a few hundred to a few thousand books. But state-of-the-art AI models, still far less capable than human brains, require many GPUs to train, and each GPU contains roughly as many transistors as the human brain contains neurons. And those state-of-the art models are being fed the equivalent of millions or even billions of books, far more than any human could ever read.

Thus, it seems likely that advances are possible both in the architectures and training methods we use to make AI models, as well as in the silicon hardware we train them on.

So, if and when significant advances in training efficiency happen, we’re going to be able to train much more capable AI models using the data, and likely the hardware, that’s already available. And soon enough — whether it’s in one year or twenty — the capabilities of AI in all analytical tasks are going to exceed those of most or all humans.

The consequences of this revolution — even extrapolating the capabilities of the technology that’s already available today, let alone that of more advanced systems — are going to be enormous, and are going to happen much more quickly than the Industrial Revolution. Unlike physical machines, AI technology can be deployed instantly to the whole world, meaning each advancement can be adopted as quickly as people can figure out how to use it, rather than being limited by the speed at which physical machines can be built and deployed.

What this implies is that much of the white-collar work that currently consists of analytical tasks — essentially, manipulating information — is going to be automated in the blink of an eye. A million people might work in data entry today — next year, that number might be zero. In a few years, when the capabilities of the technology advance, chemists or programmers might be similarly affected, and the process will continue until humans are only doing a small fraction of the analytical work that we do today.

In reality, in most lines of work, the AI won’t fully automate an entire profession — rather, it’ll reduce the amount of human effort required in that line of work by 10x, or 100x, or 1000x, just like what physical automation achieved in factories.

As a consequence, we’re going to see the raw information-processing abilities of human brains become less and less economically valuable. Technical specialists like programmers and traders, who work with self-contained purely-informational tasks, are going to see some of the biggest changes as soon as AI’s abilities exceed theirs. But most white-collar jobs contain a significant component of information processing, and are going to see that quickly handed over to the machines.

Interestingly, it seems that interpersonal relationship-oriented work is likely to be much less affected. Jobs ranging from bartender to bond salesperson rely heavily on interpersonal relationship-building, and much of the value people create in those jobs is dependent on them being people and not machines. In addition, high-end jobs that have as much to do with brokering ownership of valuable assets, power, and influence — think politicians, investment bankers, and influencers — are going to continue to be done by the people who care about accumulating that ownership, power, and influence, although those people are going to be increasingly assisted in their work by powerful AI, just as they are currently assisted by human workers.

Physical work will also be initially unaffected by the current revolution in AI — rescuing someone from a burning building or making a bed is still only possible with human hands. But the current AI revolution is increasingly looking like it’s going to unlock advances in robotics that will have a significant impact on the automation of physical work as well.

Currently, most physical-work automation is done by highly-specialized machines — walk into a reasonably-modern factory and you’ll see a number of large and expensive machines custom-tailored for jobs like bending rods or forming cans. This kind of special-purpose automation is only feasible for tasks where huge scale can be achieved in a single place — easier for tasks like manufacturing and agriculture than for tasks like house-cleaning and food-service, the need for which is naturally dispersed throughout the physical world and cannot be performed in a single place.

That said, mechanical technology is already advanced enough to make it possible to automate many of these highly-dispersed physical tasks that are still being done mostly by humans. The missing factor standing in the way of automating those tasks has rather been the intelligence available to the machines — robots have just not been smart enough to be able to do things like reliably navigate a house and manipulate a wide variety of objects.

That is all likely to change soon as the capabilities of AI continue to advance, and while the consequences will take longer to be realized in physical-world automation than with knowledge work, as they involve the manufacture and deployment of physical robots, the process will likely be faster than people expect.

This is because AI is going to unlock the wide use of a new type of automation: automation done by general-purpose hardware, whether that hardware takes the shape of humanoid robots, robot arms mounted on quadrupedal platforms, or something else entirely. And when one-size-fits-all robotic platforms powered by AI become broadly capable, they will be much cheaper and faster to manufacture and deploy than a heterogenous variety of specialized machines. This is exactly the same process thanks to which cars are now so cheap and ubiquitous — when you’re building a billion of something, you get a lot of efficiencies of scale. And when you’re building a billion general-purpose robots, which can do a wide variety of work thanks to AI, you can automate a lot of that work very quickly.

In this way, much of the work being done by people today — physical as well as analytical — is going to be increasingly done by machines. This process has already started, and is likely to accelerate over the next decade or two.

Where that leaves us humans in the economy is another question. It’s possible that a parallel process to the last 200 years may take place. Since industrialization, the physical abilities of people have become steadily less in-demand as machines have taken our places in manipulating the physical world, but through that process, the demand for our brains has only increased, causing more and more people to make a living by knowledge work as fewer and fewer make a living by physical work.

In a similar way, we may see less and less economic demand for our brains as analytical machines over the next decade or two, but to see more and more demand for our ability to relate to each other. In that kind of world, most of us will have jobs talking to each other about our needs and looking for ways to solve them — everyone a salesperson or therapist. In a world like that, brainpower will still be important, but more as a way to relate to each other than as a tool to solve complex puzzles. Incidentally, one theory of human evolution states that we evolved big brains as a result of social selection pressures that favored the survival and reproduction of those of us who were better at relating to other people — after a few hundred years of using our brains in more-analytical ways than they evolved for, we may return to a world in which our brains become useful primarily for the interpersonal tasks that they were honed by evolution to do.

But it’s also possible that AI will do such a good job at facilitating and even replacing human interactions and relationships in economic contexts (sales, customer support, etc.) that the number of humans needed for that kind of work will be far less than the number of people who will need to earn a living. In one sense, that’s a scary world — most of us will no longer be able to sustain a decent standard of living through the work we can do. But if that’s the way the world develops, the only politically feasible outcome I foresee, whether in democracies or dictatorships, is a welfare state where the work done to fulfill human needs is mostly done autonomously, and people are able to enjoy a high standard of living without working. Instead, most people would be able to spend their time on things that might not have paid the bills before, whether taking care of their families, competing at sports, traveling, painting, or any number of other things that mostly exist outside of the market economy today.

Which of those two scenarios comes to pass, or whether another one entirely will transpire, only time will tell. And whether the whittling-down of the need for knowledge work by humans takes half a decade or half a century will remain to be seen as well. But our need to work with our minds is about to go through the same winnowing process as our need to work with our bodies has experienced for the past 200 years — and it remains to be seen what the consequences will be.